When it comes to property division in a divorce case, the marital balance sheet is critical to ensuring marital assets and liabilities are accurately valued and equally divided. A correctly prepared balance sheet lists all of the parties’ assets and liabilities in one place—making it a valuable tool for shaping well-informed property division decisions. However, if prepared superficially or by inexperienced personnel, the marital balance sheet might lead attorneys and their clients to make ill-informed decisions or waste time during settlement negotiations.

Recognizing and avoiding missteps on the marital balance sheet saves clients time and money in an often already stressful divorce case. Aside from inadvertent math errors—usually the result of adding or removing rows while building out a spreadsheet or failing to double-check the math at all—the following are some other common mistakes that can occur with marital balance sheets.

1. Incorrect Allocation of Nonmarital Interest in Real Estate

Attorneys must be especially attentive to real estate that is allocated to one spouse, in which the other spouse has a nonmarital interest. In Illustration 1A below, the husband has a $50,000 nonmarital claim in real estate awarded to the wife. The fair market value of the real estate is $400,000 and the mortgage balance is $200,000.

Illustration 1A appears to give credit to the nonmarital interest. Each party receives 50% of the marital estate after the equalizer payment of $75,000 from the wife to the husband. However, Illustration 1A is inaccurate as the husband never actually receives the $50,000 he is due for his nonmarital interest in the marital residence. Though the wife appears to be allocated $350,000 in marital property, she actually receives an asset worth $400,000.

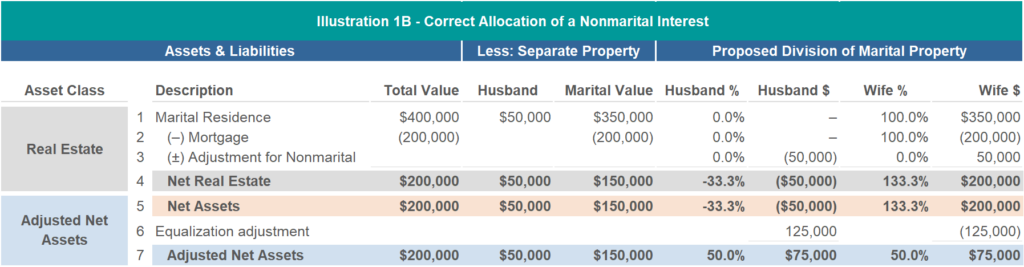

The $75,000 equalizer payment is too low without a subsequent adjustment for the husband’s $50,000 nonmarital claim in the property. Illustration 1B shows that the wife actually owes the husband an equalizer payment of $125,000:

$75,000 for net marital equity (50% times the difference between the $350,000 marital value minus the $200,000 mortgage), plus $50,000 for husband’s nonmarital interest, equals $125,000.

As the adjusted net assets in each example are equal, the adjustment on Line 3 of Illustration 1B may seem inconsequential. However, for the purpose of calculating and paying an equalizing payment, the adjustment is vital.

2. Merging Pre-Tax and After-Tax Retirement Accounts

Frequently, all of the parties’ retirement accounts are lumped within the same section of the marital balance sheet. However, aggregating the accounts in this manner could cause attorneys and their clients to conflate pre- and after-tax retirement accounts. As pre-tax retirement assets are worth less than after-tax retirement assets, failing to separately delineate between these types of accounts may lead to an unequal division of retirement assets.

When money is put into a retirement account before taxes are charged, the account is considered a pre-tax retirement account. Common pre-tax retirement accounts are 401(k) and 403(b) plans, profit-sharing plans, and traditional IRAs. Pre-tax retirement account owners receive a tax deduction when contributions are made, lowering their taxable income for that year. Then, upon withdrawal, the entire amount of the withdrawal—both the original pre-tax contributions and subsequent earnings from dividends, interest, and capital gains—are taxed as ordinary income.

On the other hand, after-tax retirement accounts—such as Roth IRAs—are funded with contributions of after-tax dollars, and any earnings grow tax-free. After-tax retirement account owners may withdraw their initial contributions at any time—for any reason—with no penalty or tax. Moreover, withdrawals of earnings are also tax-free and penalty-free if the owner has had the Roth IRA for at least five years and the withdrawal is taken when the owner is at least 59½ years old or for other qualified reasons (e.g., first-time home purchase, college expenses, birth or adoption expenses, etc.).

Illustration 2A shows how not separately delineating between pre-tax and after-tax retirement accounts on the marital balance sheet seemingly places both types of accounts on equal footing. In this scenario, the parties have $350,000 in total retirement assets, made up of $275,000 in pre-tax and $75,000 in after-tax assets. Illustration 2A allocates the assets based on the assumption that the husband’s $100,000 in pre-tax and $75,000 in after-tax retirement accounts are equal to the wife’s $175,000 in pre-tax retirement accounts.

However, based on the foregoing discussion, the husband and wife’s pre-tax and after-tax retirement accounts are not equal. Upon withdrawal, all of the wife’s retirement assets (which are pre-tax) are subject to ordinary income tax. However, for the husband, only the pre-tax portion of his assets are taxed. Illustration 2B shows how to properly delineate between the two types of accounts on the marital balance sheet.

In Illustration 2B, after the two equalizing payments, both parties receive equal amounts of pre-tax and after-tax retirement assets.

3. Failing to Delineate Unrealized Gains and Losses within a Brokerage Account

The built-in unrealized gains and losses of taxable investment accounts—also known as brokerage accounts—must be carefully delineated on the marital balance sheet. This is because the owner of the relevant assets is responsible for any capital gains and losses upon sale.

Unrealized gains and losses are calculated using the difference between the asset’s current market value and its cost basis. Cost basis is equal to the original value of an asset for tax purposes—typically, the purchase price adjusted for stock splits, dividends, and return of capital distributions.

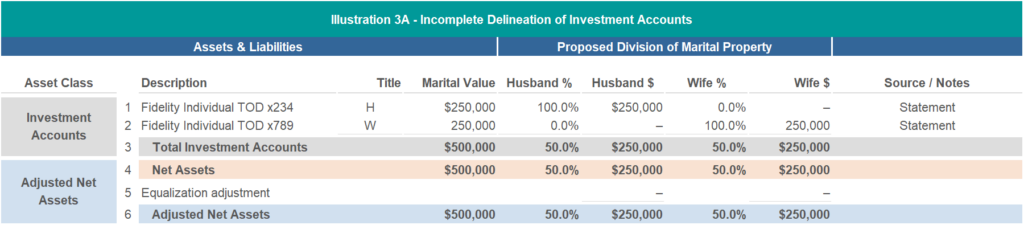

Illustration 3A depicts a scenario in which the divorcing parties have two investment accounts, each worth $250,000.

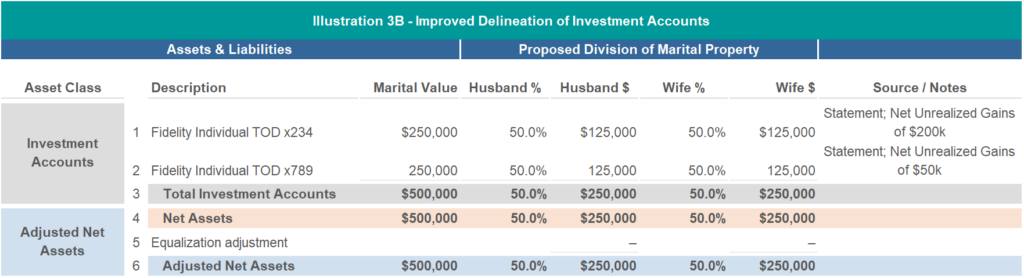

Without factoring in the built-in unrealized gains and losses, the value of the investment accounts appears to be equal. However, after reviewing the statements for each account, the amounts of unrealized gains and losses in each account are different; which should be considered for the purpose of equitable property division. As Illustration 3B demonstrates, if each party had been allocated only the investment account titled under their own name, the husband would have unknowingly received assets with significantly higher built-in gains. Taxes on these gains would be owed upon sale of the assets.

Often, to eliminate the need for a separate property settlement equalizer payment, proposed divisions of property allocate more of a brokerage account to one spouse than the other. However, it is usually best for brokerage accounts to be allocated equally (unless the account consists solely of cash balances or your financial expert calculates and shows the estimated taxes on the balance). As most brokerage accounts are made up of many types of assets—cash, equities, bonds, mutual funds and more—that each have their own cost basis, unequal allocation of the account may have inadvertent tax consequences.

Helping You Get There…

Having a qualified, experienced advisor prepare the martial balance sheet is vital to ensuring the assets are equitably divided between the divorcing parties. The financial expert provides a properly constructed balance sheet, with thoroughly identified and delineated asset values and tax liabilities, to provide clarity and neutrality to the often-emotional divorce process. Ultimately, clients and their attorneys make better-informed decisions and move forward knowing they received a fair share of assets. To talk to a qualified professional who assists with marital balance sheet preparation, contact Boulay’s Corey O’Connell, CPA/ABV, ASA today at 952.841.3025 or coconnell@boulaygroup.com.